- Home

- Patrick Rothfuss

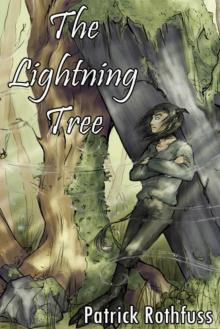

The Lightning Tree

The Lightning Tree Read online

THE LIGHTNING TREE

Patrick Rothfuss

Morning: The Narrow Road

Bast almost made it out the back door of

the Waystone Inn.

He actually had made it outside, both

feet were over the threshold and the door

was almost entirely eased shut behind

him before he heard his master’s voice.

Bast paused, hand on the latch. He

frowned at the door, hardly a handspan

from being closed. He hadn’t made any

noise. He knew it. He was familiar with

all the silent pieces of the inn, which

floorboards sighed beneath a foot, which

windows stuck …

The back door’s hinges creaked

sometimes, depending on their mood, but

that was easy to work around. Bast

shifted his grip on the latch, lifted up so

that the door’s weight didn’t hang so

heavy, then eased it slowly closed. No

creak. The swinging door was softer than

a sigh.

Bast stood upright and grinned. His

face was sweet and sly and wild. He

looked like a naughty child who had

managed to steal the moon and eat it. His

smile was like the last sliver of

remaining moon, sharp and white and

dangerous.

“Bast!” The call came again, louder

this time. Nothing so crass as a shout, his

master would never stoop to bellowing.

But when he wanted to be heard, his

baritone would not be stopped by

anything so insubstantial as an oaken

door. His voice carried like a horn, and

Bast felt his name tug at him like a hand

around his heart.

Bast sighed, then opened the door

lightly and strode back inside. He was

dark, and tall, and lovely. When he

walked he looked like he was dancing.

“Yes, Reshi?” he called.

After a moment the innkeeper stepped

into the kitchen; he wore a clean white

apron and his hair was red. Other than

that, he was painfully unremarkable. His

face held the doughy placidness of bored

innkeepers everywhere. Despite the early

hour, he looked tired.

He handed Bast a leather book. “You

almost forgot this,” he said without a hint

of sarcasm.

Bast took the book and made a show of

looking surprised. “Oh! Thank you,

Reshi!”

The innkeeper shrugged and his mouth

made the shape of a smile. “No bother,

Bast. While you’re out on your errands,

would you mind picking up some eggs?”

Bast nodded, tucking the book under his

arm. “Anything else?” he asked dutifully.

“Maybe some carrots too. I’m thinking

we’ll do stew tonight. It’s Felling, so

we’ll need to be ready for a crowd.” His

mouth turned up slightly at one corner as

he said this.

The innkeeper started to turn away, then

stopped. “Oh. The Williams boy stopped

by last night, looking for you. Didn’t

leave any sort of message.” He raised an

eyebrow at Bast. The look said more

than it said.

“I haven’t the slightest idea what he

wants,” Bast said.

The innkeeper made a noncommittal

noise and turned back toward the

common room.

Before he’d taken three steps Bast was

already out the door and running through

the early-morning sunlight.

By the time Bast arrived, there were

already two children waiting. They

played on the huge greystone that lay

half-fallen at the bottom of the hill,

climbing up the tilting side of it, then

jumping down into the tall grass.

Knowing they were watching, Bast took

his time climbing the tiny hill. At the top

stood what the children called the

lightning tree, though these days it was

little more than a branchless trunk barely

taller than a man. All the bark had long

since fallen away, and the sun had

bleached the wood as white as bone. All

except the very top, where even after all

these years the wood was charred a

jagged black.

Bast touched the trunk with his

fingertips and made a slow circuit of the

tree. He went deasil, the same direction

as the turning sun. The proper way for

making. Then he turned and switched

hands, making three slow circles

widdershins. That turning was against the

world. It was the way of breaking. Back

and forth he went, as if the tree were a

bobbin and he was winding and

unwinding.

Finally he sat with his back against the

tree and set the book on a nearby stone.

The sun shone on the gold gilt letters,

Celum Tinture. Then he amused himself

by tossing stones into the nearby stream

that cut into the low slope of the hill

opposite the greystone.

After a minute, a round little blond boy

trudged up the hill. He was the baker’s

youngest son, Brann. He smelled of

sweat and fresh bread and … something

else. Something out of place.

The boy’s slow approach had an air of

ritual about it. He crested the small hill

and stood there for a moment quietly, the

only noise coming from the other two

children playing below.

Finally Bast turned to look the boy

over. He was no more than eight or nine,

well dressed, and plumper than most of

the other town’s children. He carried a

wad of white cloth in his hand.

The boy swallowed nervously. “I need

a lie.”

Bast nodded. “What sort of lie?”

The boy gingerly opened his hand,

revealing the wad of cloth to be a

makeshift bandage, spattered with bright

red. It stuck to his hand slightly. Bast

nodded; that was what he’d smelled

before.

“I was playing with my mum’s knives,”

Brann said.

Bast examined the cut. It ran shallow

along the meat near the thumb. Nothing

serious. “Hurt much?”

“Nothing like the birching I’ll get if she

finds out I was messing with her knives.”

Bast nodded sympathetically. “You

clean the knife and put it back?”

Brann nodded.

Bast tapped his lips thoughtfully. “You

thought you saw a big black rat. It scared

you. You threw a knife at it and cut

yourself. Yesterday one of the other

children told you a story about rats

chewing off soldier’s ears and toes while

they slept. It gave you nightmares.”

Brann gave a shudder. “Who told me

/>

the story?”

Bast shrugged. “Pick someone you

don’t like.”

The boy grinned viciously.

Bast began to tick off things on his

fingers. “Get some blood on the knife

before you throw it.” He pointed at the

cloth the boy had wrapped his hand in.

“Get rid of that, too. The blood is dry,

obviously old. Can you work up a good

cry?”

The boy shook his head, seeming a little

embarrassed by the fact.

“Put some salt in your eyes. Get all

snotty and teary before you run to them.

Howl and blubber. Then when they’re

asking you about your hand, tell your

mum you’re sorry if you broke her knife.”

Brann listened, nodding slowly at first,

then faster. He smiled. “That’s good.” He

looked around nervously. “What do I

owe you?”

“Any secrets?” Bast asked.

The baker’s boy thought for a minute.

“Old Lant’s tupping the Widow Creel

…” he said hopefully.

Bast waved his hand. “For years.

Everyone knows.” Bast rubbed his nose,

then said, “Can you bring me two sweet

buns later today?”

Brann nodded.

“That’s a good start,” Bast said. “What

have you got in your pockets?”

The boy dug around and held up both

his hands. He had two iron shims, a flat

greenish stone, a bird skull, a tangle of

string, and a bit of chalk.

Bast claimed the string. Then, careful

not to touch the shims, he took the

greenish stone between two fingers and

arched an eyebrow at the boy.

After a moment’s hesitation, the boy

nodded.

Bast put the stone in his pocket.

“What if I get a birching anyway?”

Brann asked.

Bast shrugged. “That’s your business.

You wanted a lie. I gave you a good one.

If you want me to get you out of trouble,

that’s something else entirely.”

The baker’s boy looked disappointed,

but he nodded and headed down the hill.

Next up the hill was a slightly older

boy in tattered homespun. One of the

Alard boys, Kale. He had a split lip and

a crust of blood around one nostril. He

was as furious as only a boy of ten can

be. His expression was a thunderstorm.

“I caught my brother kissing Gretta

behind the old mill!” he said as soon as

he crested the hill, not waiting for Bast to

ask. “He knew I was sweet on her!”

Bast spread his hands helplessly,

shrugging.

“Revenge,” the boy spat.

“Public revenge?” Bast asked. “Or

secret revenge?”

The boy touched his split lip with his

tongue. “Secret revenge,” he said in a

low voice.

“How much revenge?” Bast asked.

The boy thought for a bit, then held up

his hands about two feet apart. “This

much.”

“Hmmmm,” Bast said. “How much on a

scale from mouse to bull?

The boy rubbed his nose for a while.

“About a cat’s worth,” he said. “Maybe a

dog’s worth. Not like Crazy Martin’s dog

though. Like the Bentons’ dogs.”

Bast nodded and tilted his head back in

a thoughtful way. “Okay,” he said. “Piss

in his shoes.”

The boy looked skeptical. “That don’t

sound like a whole dog’s worth of

revenge.”

Bast shook his head. “You piss in a cup

and hide it. Let it sit for a day or two.

Then one night when he’s put his shoes

by the fire, pour the piss on his shoes.

Don’t make a puddle, just get them damp.

In the morning they’ll be dry and

probably won’t even smell too much …”

“What’s the point?” the boy interrupted

angrily. “That’s not a flea’s worth of

revenge!”

Bast held up a pacifying hand. “When

his feet get sweaty, he’ll start to smell

like piss.” Bast said calmly. “If he steps

in a puddle, he’ll smell like piss. When

he walks in the snow, he’ll smell like

piss. It will be hard for him to figure out

exactly where it’s coming from, but

everyone will know your brother is the

one that reeks.” Bast grinned at the boy.

“I’m guessing your Gretta isn’t going to

want to kiss the boy who can’t stop

pissing himself.”

Raw admiration spread across the

young boy’s face like sunrise in the

mountains. “That’s the most bastardly

thing I’ve ever heard,” he said,

awestruck.

Bast tried to look modest and failed.

“Have you got anything for me?”

“I found a wild beehive,” the boy said.

“That will do for a start,” Bast said.

“Where?”

“It’s off past the Orissons’. Past

Littlecreek.” The boy squatted and drew

a map in the dirt. “You see?”

Bast nodded. “Anything else?”

“Well … I know where Crazy Martin

keeps his still …”

Bast raised his eyebrows at that.

“Really?”

The boy drew another map and gave

some directions. Then he stood and

dusted off his knees. “We square?”

Bast scuffed his foot in the dirt,

destroying the map. “We’re square.”

The boy dusted off his knees, “I’ve got

a message too. Rike wants to see you.”

Bast shook his head firmly. “He knows

the rules. Tell him no.”

“I already told him,” the boy said with

a comically exaggerated shrug. “But I’ll

tell him again if I see him …”

There were no more children waiting

after Kale, so Bast tucked the leather

book under his arm and went on a long,

rambling stroll. He found some wild

raspberries and ate them. He took a drink

from the Ostlar’s well.

Eventually Bast climbed to the top of a

nearby bluff where he gave a great

stretch before tucking the leather-bound

copy of Celum Tinture into a spreading

hawthorn tree where a wide branch made

a cozy nook against the trunk.

He looked up at the sky then, clear and

bright. No clouds. Not much wind. Warm

but not hot. Hadn’t rained for a solid

span. It wasn’t a market day. Hours

before noon on Felling …

Bast’s brow furrowed a bit, as if

performing some complex calculation.

Then he nodded to himself.

Then Bast headed back down the bluff,

past Old Lant’s place and around the

brambles that bordered the Alard farm.

When he came to Littlecreek he cut some

reeds and idly whittled at them with a

small bright knife. Then brought the

string out of

his pocket and bound them

together, fashioning a tidy set of

shepherd’s pipes.

He blew across the top of them and

cocked his head to listen to their sweet

discord. His bright knife trimmed some

more, and he blew again. This time the

tune was closer, which made the discord

far more grating.

Bast’s knife flicked again, once, twice,

thrice. Then he put it away and brought

the pipes closer to his face. He breathed

in through his nose, smelling the wet

green of them. Then he licked the fresh-

cut tops of the reeds, the flicker of his

tongue a sudden, startling red.

Then he drew a breath and blew against

the pipes. This time the sound was bright

as moonlight, lively as a leaping fish,

sweet as stolen fruit. Smiling, Bast

headed off into the Bentons’ back hills,

and it wasn’t long before he heard the

low, mindless bleat of distant sheep.

A minute later, Bast came over the crest

of a hill and saw two dozen fat, daft

sheep cropping grass in the green valley

below. It was shadowy here, and

secluded. The lack of recent rain meant

the grazing was better here. The steep

sides of the valley meant the sheep

weren’t prone to straying and didn’t need

much looking after.

A young woman sat in the shade of a

spreading elm that overlooked the valley.

She had taken off her shoes and bonnet.

Her long, thick hair was the color of ripe

wheat.

Bast began playing then. A dangerous

tune. It was sweet and bright and slow

and sly.

The shepherdess perked up at the sound

of it, or so it seemed at first. She lifted

her head, excited … but no. She didn’t

look in his direction at all. She was

merely climbing to her feet to have a

stretch, rising high up onto her toes,

hands twining over her head.

Still apparently unaware she was being

serenaded, the young woman picked up a

nearby blanket, spread it beneath the tree,

and sat back down. It was a little odd, as

she’d been sitting there before without

the blanket. Perhaps she’d just grown

chilly.

Bast continued to play as he walked

down the slope of the valley toward her.

He did not hurry, and the music he made

was sweet and playful and languorous all

at once.

The shepherdess showed no sign of

noticing the music or Bast himself. In fact

she looked away from him, toward the

far end of the little valley, as if curious

what the sheep might be doing there.

When she turned her head, it exposed the

The Slow Regard of Silent Things

The Slow Regard of Silent Things The Name of the Wind

The Name of the Wind The Wise Man's Fear

The Wise Man's Fear The Lightning Tree

The Lightning Tree The Slow Regard of Silent Things: A Kingkiller Chronicle Novella (The Kingkiller Chronicle)

The Slow Regard of Silent Things: A Kingkiller Chronicle Novella (The Kingkiller Chronicle)![Kingkiller Chronicle [01] The Name of the Wind Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/kingkiller_chronicle_01_the_name_of_the_wind_preview.jpg) Kingkiller Chronicle [01] The Name of the Wind

Kingkiller Chronicle [01] The Name of the Wind The Name of the Wind tkc-1

The Name of the Wind tkc-1